I have long been inspired by the songs and message of the musical Hamilton. There is a moment in the show when the titular character faces an hour of maximum crisis, when it seems like his world is crumbling. He sings of being in the eye of a hurricane, before declaring “I’ll write my way out,” expressing his intent to use words to both process the chaotic moment and also, hopefully, find some deliverance from it.

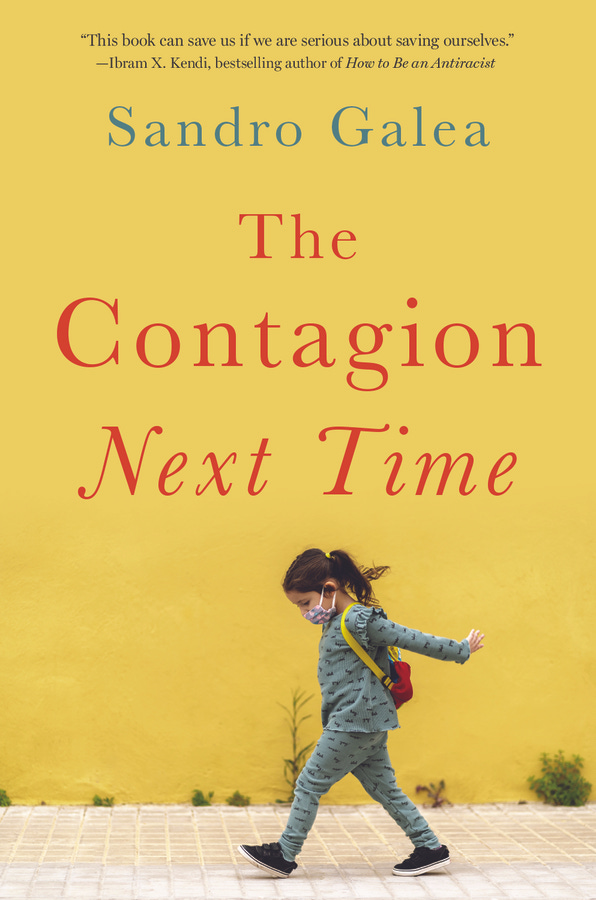

That moment particularly resonated with me. I have long turned to writing to make sense of challenging events, and to try to inform a conversation that helps support a better future. And, in recent years, we have all known what it is to feel like we are in the eye of a storm. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a tempest, turning our world upside down, radically changing how we live. We have all processed the pandemic differently. My way has been writing. During the crisis, I wrote about why we found ourselves in the situation we were in, and what it will take to avoid another, potentially worse, pandemic. Those writings became my new book, The Contagion Next Time, which will be out Monday.

While working on the book, I occasionally encountered the question—from others, or posing it to myself—why write about a pandemic during a pandemic? Is it not enough simply to engage with the difficult, day-to-day work of trying to navigate the moment? Why also take on a book project? Was it solely to “write my way out,” to make sense of what at times seemed senseless, to cope with the grief of the moment? Such motives are necessary but not sufficient explanations for why I wrote The Contagion Next Time. It is true that I did so to process, to cope. But I also did so because it seemed like our conversation about COVID-19 was missing something important. For roughly two years, the pandemic was just about all we talked of. We discussed the nature of the virus itself, its effect on our lives, the treatments we hoped could help make a difference, and the vaccines that have done much to return us to some semblance of normalcy. What we have not discussed, however—at least, not as much as we should—are the underlying causes of the pandemic.

Now, some may read that and say “This is not true. The pandemic was caused by a virus and we discussed that at length.” It is true that COVID-19 was the precipitating factor for the catastrophe of 2019—2021. But the fundamental cause, I would argue, is deeper than that. It is the fact that, in the US, Black people live shorter, sicker lives than white people. It is people living in dilapidated, rundown neighborhoods with mold in their walls making them sick. It is economic inequality that lets some people work remotely in comfortable suburbs during a pandemic, while others must brave daily interactions with crowds at a low-wage job they are terrified of losing. It is disinvestment in a social safety net that could have provided greater support for those in need when COVID-19 struck. It is a culture of division which stopped us from cohering around concern for the common good at a moment of historic crisis. It is the full range of social, economic, environmental, and political conditions that created a world that is nowhere near as healthy as it should, and could, be. These conditions created reservoirs of poor health in our society which long predated the pandemic, amounting to a tinderbox in which circumstance dropped the lit match of COVID-19.

But, for all the destruction it caused, the fire of the pandemic was not like a real fire in one key respect. When a real fire takes hold, it eventually burns out the conditions that made it possible. In the case of COVID-19, the conditions that helped the disease become a conflagration are no less poised to burn now than they were in the summer of 2019. The same inequities, injustices, and misalignment of our collective priorities remain, waiting for the next spark.

When that spark comes—and it will come—there is no guarantee it will not be far worse than what we have just experienced. COVID-19, for all the damage it did, was not a very lethal disease. This is particularly true when we compare it to pandemics of the past—both the distant past (the Black Death) and the recent past (SARS, a disease with much in common with COVID-19, less infectious but with a greater capacity to kill those it infects). Addressing the underlying causes of the pandemic, then, is a matter of existential importance. If our conversation about COVID-19 merely scratches the surface—focusing on the virus and its treatments rather than on the conditions that allowed the contagion to take hold—we are putting ourselves in a dangerous position. I titled the book The Contagion Next Time as a tribute to James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. Baldwin’s title warns of a conflagration coming to engulf American society if we do not fully address racial injustice. Like Baldwin’s fire, the contagion next time will be precisely as destructive as we allow it to be. We have a choice. We can learn the lessons of the last pandemic in order to prevent the next one or we can neglect the danger we still face, and suffer the worst when it comes.

What does it mean to learn the lessons of the pandemic? It means nothing less than the creation of a better world, one that is maximized for health. This will take sustained, collective engagement with the foundational drivers of health. Often, what we think is engagement with these drivers is actually engagement with doctors and medicines—the treatments that help us when we are sick but do little to shape whether or not we get sick in the first place. This narrow focus has also characterized our conversation about COVID-19. We have talked about vaccines, we have talked about therapeutics, we have talked about finding ways to stop viruses from jumping from bats to humans, but we have not talked as much about the structural forces that made COVID-19 what it became. This also applies for the books that have emerged about the pandemic. Many have tackled the medical side of COVID-19, and they have been worthwhile reads. But The Contagion Next Time is not one of those books. It aims to express a vision for a world where we have addressed the underlying issues that leave us vulnerable to pandemics, to prevent disease from taking hold.

It is worth noting that, when I began writing The Contagion Next Time in the summer of 2020, I, like everyone else, did not know when the pandemic would end. But I did know how it would likely behave. I knew it would probably exploit the poor health that has long existed in our society, because that is what infectious threats do. They spread among the vulnerable, the marginalized, those whose lives have set them up for poor health. COVID-19 was no different. Once again, a broken status quo, caused by our failure to invest in health as a public good, created the conditions for falling short in the face of a virus. It did not have to be this way. Our failure was the product of a choice we made, a choice not to engage with the underlying causes of poor health, to turn a blind eye to the marginalized, to let our collective vulnerability go unaddressed. We cannot afford to make this mistake again.

The Contagion Next Time aspires to help inform a conversation that points our focus towards what matters most for health, so we can address these core factors and do right by this moment, to ensure that the worst is behind us. The observations and arguments in the book emerged from a perspective informed by a career working in public health, by the unique challenges of the COVID-19 moment, and by conversations with colleagues and friends. I am grateful indeed to the many whose thoughts helped sharpen my own.

As we move towards a post-COVID-19 future, we have a chance to not merely return to something like the pre-pandemic status quo, but to build a world that is better, by far, than the one that first faced a novel coronavirus in 2019. If we engage with what matters most for health, if we invest in improving the structural drivers of health and disease, we can get to a world that is unrecognizable in the best of ways. If we dither, if we forget, if we neglect the hard lessons of the moment, we could face a disaster unlike anything we have seen in our lifetimes. Why did I write a book about a pandemic during a pandemic? Fundamentally, it was to help make sure that the COVID-19 moment is the last time anyone ever needs to do so.

__ __ __

Also.

In this week’s The Turning Point, Michael Stein and I ask: when might we stop counting COVID-19 cases so visibly and balance our awareness of the virus with attention to the full range of health challenges around us?

This week in Nature Human Behavior, I share thoughts on shaping a science for better decision-making in future crises. In the RWJF Culture of Health Blog, I wrote on how love and hate influence health and racial equity. And in the Boston Globe, a group of leaders of schools and programs of public health and I wrote an op-ed about integrating health equity into all state policies, starting with Massachusetts.

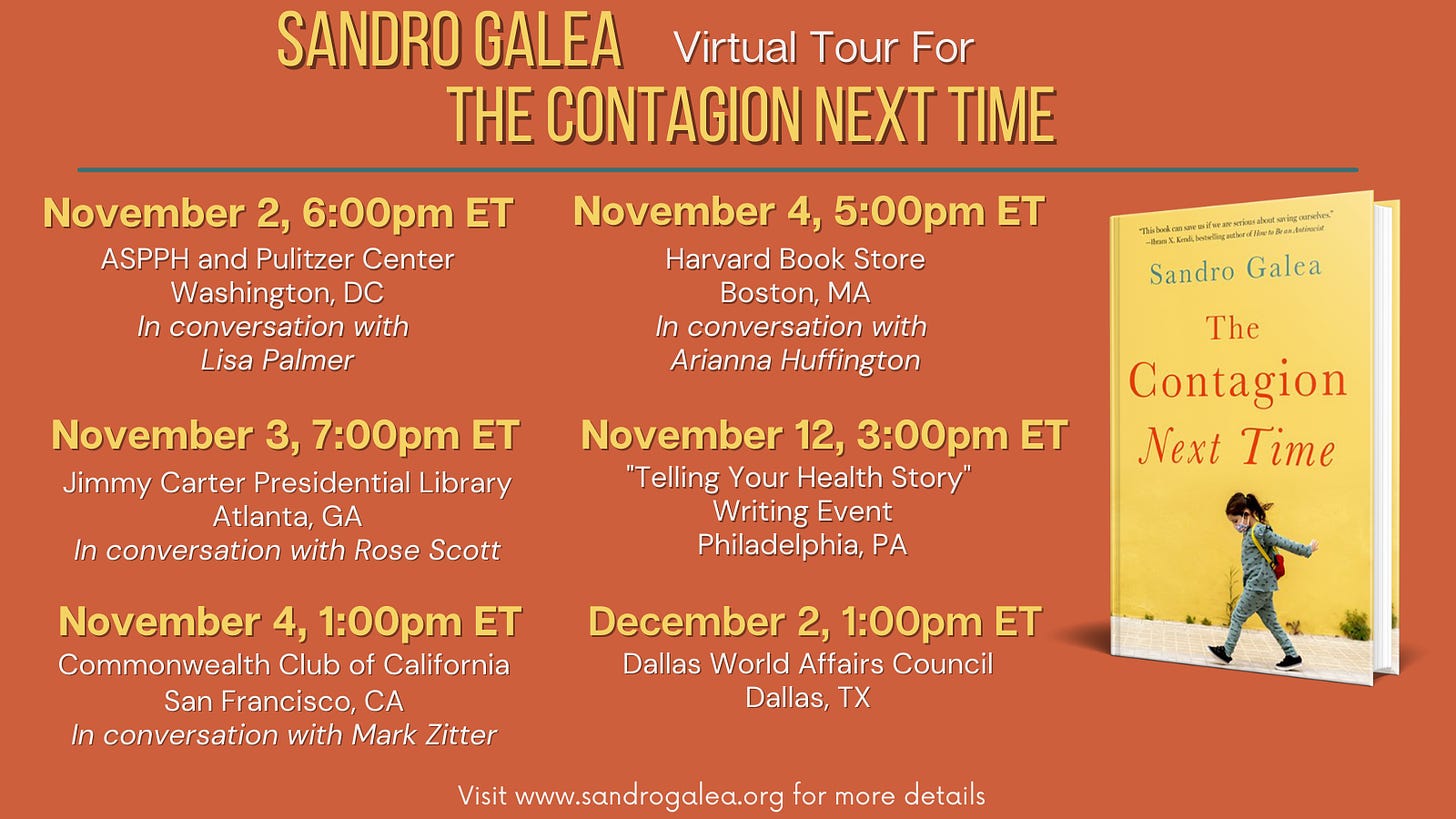

It is also hard to believe we are just two days away from the November 1 launch of The Contagion Next Time. Coming up this week will be a series of events around the book, including a Reddit Ask Me Anything (AMA) on Monday from 12 - 2 pm, a book talk in Washington D.C. with ASPPH and the Pulitzer Center, and virtual book talks across the country (zoom backgrounds tbd).

Thank you for joining me on this journey.

I ordered the book from a local store and picked it up yesterday. The particular problem I'm interested in is how we link our everyday interests in maintaining shelter and financial security with our communitarian principles for widespread wellbeing. How do we grasp that we---I, you, and they--- all do better when we---I, you, and they--- do better?