The consent of the governed

What the conversation about COVID-19 vaccines can teach us about how to navigate the social compact between voices of authority and the populations they serve.

Over the last year or so there has been much criticism of leadership in the U.S. for the state of affairs in this country. Government at the local and national level has been criticized for failures in mitigating COVID-19 and for challenges in addressing any number of the problems we collectively face. Such criticism is often warranted, helpful even. Power needs accountability, so that it can be used most effectively to support the common good (see prior thoughts on how accountability can help ensure effective functioning within bureaucracies). However, it strikes me that in much of this criticism there is an implicit belief that people in positions of leadership have more power than they actually do to sway events. We seem to believe that there is somewhere a magic wand which can be waved to solve our problems, and that it is only some kind of obstinacy which stops those in power from waving it.

This belief reflects a lack of understanding, on our part, of the extent to which the capacity of leadership to do, well, anything, depends on us—on the consent of the governed. In my writing, including in my upcoming book, The Contagion Next Time, I have found myself returning to a telling quote from Abraham Lincoln, “[P]ublic sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it, nothing can succeed.” The power of public opinion is such that even a relatively low level of public engagement can be enough to reshape society. Research has suggested that it takes about 3.5 percent of a population actively engaging in political protests to bring about real political change.

Given this power, if the public withholds its consent from a given measure, governments face a steep uphill climb towards the measure’s successful implementation. It does not matter how much good the measure might do; without the consent of the governed, it cannot take effect to any significant degree. When this ineffectiveness occurs, it can look like it is solely the fault of incompetent leadership, when, in fact, leadership may be doing all it can within the confines of withheld public consent.

This consent is more than just the linchpin of effective policy. It is, arguably, the cornerstone of the entire philosophy of liberal governance, refined during the Enlightenment notably by the political philosopher John Locke, which forms the basis for our political system in the U.S. According to Locke, the basis for this consent was the understanding that the people would willingly surrender some of their rights to the government in exchange for that government safeguarding life, liberty, property rights, and the public good. This arrangement was regarded as provisional, reserving for the people the right to resist any government that did not uphold the social contract.

We see reflections of this contract throughout our society. Take the example of traffic laws, in which we surrender to these laws our ability to navigate the open road at whatever speed we wish, with the understanding that doing so will keep us, and those around us, safer. The power of this social contract is well-reflected by the way we abide by it even in the absence of heavy-handed enforcement mechanisms. How often, for example, do you sit at a stoplight at night, with no one around? Why do you not speed through it? The answer is likely, in part, because you believe that consenting to the rules is better for all of us, that the system of regulations of which the stoplight is a reflection helps support a better, healthier world in clearly tangible ways.

But what if we stop believing this? What happens when, rightly or wrongly, we no longer trust those who hold power to uphold their end of the social contract? We need not look far for answers—we are seeing what happens among those who are resisting COVID vaccination. Large numbers of people are withholding their consent; not only that, they are withholding it on an issue where their consent can make the difference between life and death. They are choosing, it might be said, to speed through the traffic lights, despite the risk and the urgings of the common good. The question is: why?

It seems to me that there are three key reasons. The first is lack of trust. Many people simply do not believe the government has their best interests at heart. Examples of political dishonesty, both real and imagined, have only exacerbated this belief. At present, much of the most vocal distrust around vaccines is concentrated on the political right. However, it is worth remembering that, early in the pandemic, some on the political left expressed skepticism of any vaccine developed under the aegis of the Trump administration, given the administration’s record of false and misleading statements. This reflects how distrust can spread across the political spectrum, and that leaders should be wary of adding to it by engaging in willfully misleading behavior.

This leads to a second threat to the integrity of the social contract: the cynical exploitation of societal divisions by political actors. Implicit in the social contract between the people and the government is the understanding that both parties will attempt to behave responsibly, guided by reason and a pragmatic concern for the public good. It is a delicate balance, which is always vulnerable to those who would exploit the status quo in the name of gaining personal power. Societal division has always existed, but a responsible leader, working within the liberal order, will work to bridge these divides, or, at least, to not inflame them. Unfortunately, some will choose to do the opposite, calculating the path of the demagogue to be a quicker route to prominence than that of the measured consensus-builder. There is a long tradition of such figures in the U.S., and they have thrived in recent years, the internet making it easier than ever to cultivate and monetize large followings based on whatever compels attention, even when this comes at the expense of the public good. Such figures help to further polarize the spread of information, making it increasingly difficult to know who or what to believe.

In doing so, these figures often make use of misinformation. This is the third key challenge to maintaining the consent of the governed. If a debate is polluted by misinformation, it does not matter how well-reasoned the logic of leadership is, it will always face the obstacle of falsehoods masquerading as facts. It strikes me that misinformation requires two key factors in order to thrive: first, it needs figures unscrupulous enough disseminate it. Second, it needs a context in which established authorities have indeed been occasionally dishonest or, at least, inconsistent in their messaging. Such failures open the door to those who would say that truth is relative, or that the occasional missteps of those in positions of authority mean nothing they say should be trusted.

What do these challenges to the social contract, and to the consent of the governed, teach us about how we should talk about health, to encourage healthy behaviors in the years to come?

First, they teach us the importance of trust. For populations to consent to measures meant to improve public health, they must trust the people who are recommending them. For those of us trying to promote these measures, this means, frankly, being trustworthy. This does not just mean not telling lies, it means not giving the appearance of telling lies by being evasive, unclear, or inconsistent in our communication. During COVID, for example, it could sometimes seem like some of us used our mandate to follow the data as a crutch for inconsistent communication. If we contradicted ourselves, we could simply say we did so because the data changed. Now, sometimes the data really did change. Other times, however, it did not, but perhaps the political or social incentives had, causing us to reverse a position or walk back prior statements. Regardless of whether or not we were justified in claiming changing data as the reason for these reversals, such behavior can seem dishonest, eroding the consent on which we rely for our message to resonate.

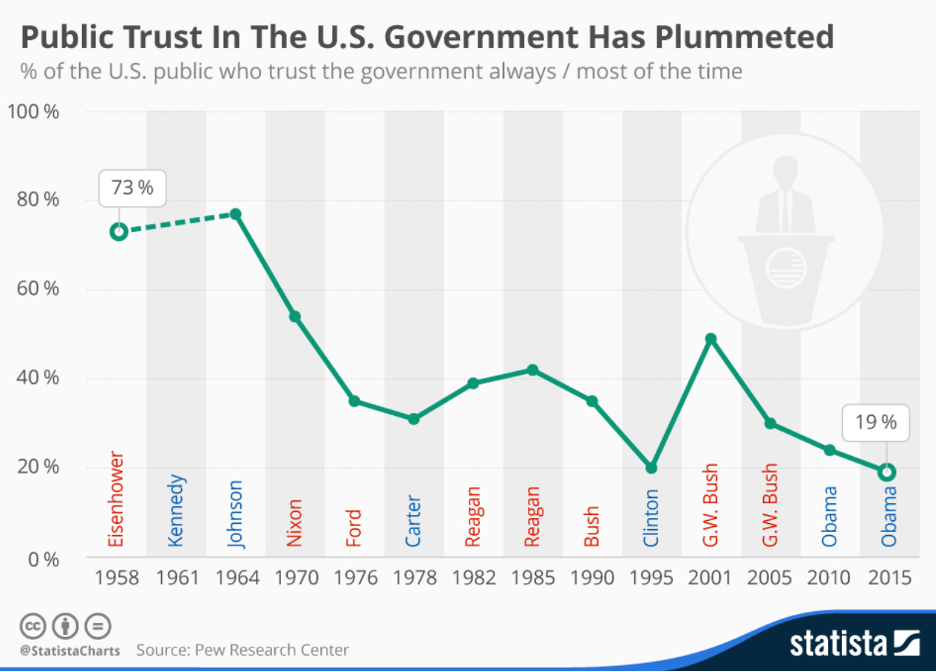

It is particularly important to build and maintain trust in the current context, where trust in institutions has been eroding across the board. The chart below, for example, shows the decline in trust in government over about 55 years. It reflects a sea change: where once the public was primed, for the most part, to trust those in power, the assumption now appears to have swung the other way, with those in power regarded as dishonest until proven trustworthy. With this in mind, it is important to place a premium on supplying this proof.

Source: McCarthy N. Public Trust In The U.S. Government Has Plummeted. Statista Web site. https://www.statista.com/chart/4054/public-trust-in-the-us-government-has-plummeted/. Published November 24, 2015. Accessed August 30, 2021.

Second, we should take care not to overplay our hand when it comes to what we ask of the public. In politics, the consent of the governed depends on a delicate balance, with the people making sacrifices with the expectation of clearly defined benefits. Such a balance also defines public health. We ask populations to make certain sacrifices, and to accept our coordination of these sacrifices at the institutional level, so that they might gain the benefit of better health.

We are at our best in this context when we are clear with the public about why we are asking what we are asking, about how long we are asking it for, and about why this duration is necessary. When we are unsure about any of this, we have a responsibility to be honest about it, even if we feel this might undercut our authority—if it does, it will surely not do so more than if we seem to be dishonest or unduly political in our recommendations.

At core, supporting a social contract that relies on the consent of the governed means prioritizing engagement with the needs and perspectives of the populations we serve—something which should be guiding our efforts at all times. Encouraging healthy behaviors requires transparency about why these behaviors are necessary, and the understanding that the public’s buy-in is always provisional and should not be taken for granted or abused. For the public to uphold their end of the contract, we must uphold ours, working collaboratively and respectfully towards a healthier world for all.

__ __ __

Also.

In this week’s The Turning Point, Michael Stein and I write about how our expectations shape our perception of reality.

Also, colleagues and I published a description in Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology of a long-term research project that assesses the mental health of Ohio Army National Guard members. Thank you to the team for their ongoing work and to Laura Sampson in particular for leading on this.

This past week we launched our Fall public programming, including conversations with global leaders on population health priorities in major regions of the world as part of the Rockefeller Foundation-Boston University 3-D Commission. Please do sign up for our upcoming conversations and programming.

On this, the 20th anniversary of September 11th, I offer some comments on what we have learned since the fateful day.

Tomorrow marks the 50-day mark before the publication of The Contagion Next Time. Thank you to all who have ordered early copies so far.

Such a thoughtul post.

It struck me that in addition to the first factor of misinformation noted, unscrupulous actors, we also have truly well-meaning individuals who believe unsubstantiated statements and who disseminate misinformation in order to "help" or "protect" others in their social circles.