The aesthetics of a healthier world

Using the tools of art and metaphor to shape a new vision of health.

As we enter the Sunday of Summer, I wanted today to muse on a somewhat lighter topic than ones I have taken on of late—namely the aesthetics of a healthier world. Public health is an aspiration as much as it is a technical set of skills, tasks, and methodologies. It is, at core, the pursuit of a vision—a vision of a healthier world. This pursuit is more than a technical process. It is an imaginative, creative endeavor. It requires us to radically rethink what the world could be, so that our aspirations might support a future which is far better than our past. To imagine a radically healthier world is to imagine a world unlike one we have yet seen. Lacking this frame of reference means we need to draw on our creative capacities in envisioning this future. Doing so takes us beyond the realm of purely technical considerations, and into that of art and metaphor. I recently wrote the introduction to an “Arts and Public Health” supplement for the journal Health Promotion Practice. I am grateful to the editors for affording me a chance to think more about how art reflects and informs the forces that shape health. This Healthiest Goldfish is, in part, inspired by these prior reflections on the interplay of art and health and the work of many who have written on this topic. Leaning for a moment on the work of Leonard Bernstein who once said:

“Any great work of art…revives and readapts time and space, and the measure of its success is the extent to which it makes you an inhabitant of that world, the extent to which it invites you in and lets you breathe its strange, special air.”

This speaks to how art, through its aesthetic power, can shape a vision of a different world, one which invites the public to engage with new possibilities for how life could be. Is there any reason why the pursuit of health should be less visionary? Bernstein was a master of working within the medium of music to transport listeners to another place. His music for West Side Story, for example (with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim), takes those who hear it to an impressionistic, almost dreamlike version of New York City, which serves as the canvas for a tale of tragedy and young love. If such care can be taken to craft a fictional world for audiences to enjoy, public health, which seeks to create a new world in a literal sense, should be just as comfortable working within aesthetic domains as it is engaging with the more tangible aspects of our field.

So, turning to health, it is first worth asking: what do we mean by aesthetics? It is easy to think aesthetic sensibilities amount simply to taste, and, in a sense, they do. Aesthetic power speaks to our perceptions of beauty, animating our sense of the lovely, the transcendent. This sense is deeply personal. While there is much that we have come to collectively regard as beautiful—nature, for example, and certain works of art—fundamentally, whether or not something is beautiful lies in the eye of the individual beholder. Yet the fact that we perceive beauty at all, regardless of our opinion of particular sights, sounds, and experiences, speaks to a deeper truth about aesthetics: they reflect fundamental values; that of beauty and that of truth. John Keats, one of my favorite romantic poets, closed his poem, Ode on a Grecian Urn, with the lines, "’Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.’" This implies that when we experience aesthetic delight, we are, at core, relishing an encounter with truth. We love a play or film because it conveys something true about the human experience; we enjoy visual art because it provides a window into a truth about our reality, one we may have missed; we love music for reasons which echo Harlan Howard’s definition of country music as “three chords and the truth.” We value beauty because we value truth; this is at the core of aesthetic experience. In valuing truth, art and aesthetics share much in common with the science at the heart of public health.

An aesthetic for a healthier world, then, is one which reflects the truth about health. The current aesthetic of health does not always fully convey this truth. What are the sights and sounds of health? Likely, what first comes to mind are images of people exercising—perhaps a workout montage set to music from a film like Creed. Then there are young, vibrant faces beaming with fitness. Perhaps we also imagine the logo of some health food or sports drink, or the slogan of a trendy sneaker company. This is an appealing aesthetic, but is it the truth? We in public health know it is not. It is a slickly packaged presentation of a highly individualized version of the pursuit of health, which does not consider the socioeconomic forces that are, in fact, the overwhelming drivers of health and disease in our society. This aesthetic also, in its focus on youth, leaves out the rest of the life-course, suggesting health is primarily something for the young, whereas the truth is that, as populations age, maximizing health becomes a project which increasingly concerns those at the mid- and later-stage of life. It is also true that a healthier world is indeed one where people live longer, healthier lives, reiterating the importance of an aesthetic which captures the experience of older adults as stylistically as it captures the comings and goings of youth.

Such an aesthetic could well take inspiration from the many older adults who have thrived in the field of art, enriching our world through their creativity. There is the renowned pianist Martha Argerich, for example, who, at the age of 80, continues to play complex pieces, from memory, with as much skill as she ever has. Then there is Françoise Gilot, who, at age 99, continues to produce masterful visual art. Or, to remain in the world of painters, there was Georgia O’Keeffe, who lived to be 98, and painted well into her older years. These women reflect how advanced age can be a time of even greater poise and productivity in one’s art than the years that preceded it. An aesthetic shaped by such examples can indeed support a new vision of what it means to live a healthier life.

In considering this aesthetic, it is also necessary to ask if we are being sufficiently inclusive in our representations of a long, healthy life. A healthier world is one where everyone lives longer, healthier lives, regardless of race, sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. Depicting such a world means more than just featuring people of different backgrounds in our cultural depictions of health. It means declining to traffic in stereotypes around who gets sick and why. It is, of course, true that certain demographic groups feel more acutely the burden of certain diseases; this reality is core to the study of health disparities. But this should be depicted accurately, as a product of foundational socioeconomic forces, rather than as somehow a failing intrinsic to certain groups. It is an unfortunate fact, for example, that, for a long time, LGBTQ characters were depicted in film, television, and literature, as fundamentally tragic, often dying by the end of the story. This was also frequently the case in portrayals of biracial characters. The aesthetics of a healthier world would counter these stereotypes, representing these populations in ways which better reflect the truth about their lives. This does not mean that the aesthetics of a healthier world should shy away from the tragic aspects of population health, only that depicting this reality should include an accurate view of all who suffer from poor health, rather than focusing on a single, stigmatized group.

Finally, the aesthetics of a healthier world should incorporate art which depicts the path from where we are to where we hope to be. One of the most affecting examples of such art, to me, has long been Tony Kushner’s play, Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. I remember clearly the first time I saw the play at a time in my life when I was practicing clinical medicine. It felt like a representation in poetry of the prose of reality. It is a play which depicts the darkness of the HIV/AIDS crisis in a way that does not stigmatize its victims, or flinch at depicting the social forces which threatened them, while offering a near-mystical vision of how society might be transformed—indeed, transfigured—into a healthier, more just and inclusive place. There is no substitute for seeing the play in its entirety, or watching the film, but a brief summation of its power to conjure a better world is captured in its closing speech, delivered by the protagonist Prior Walter (watch here). The play premiered in the early nineties, a time when the end of AIDS and full social equality for the LGBTQ population still seemed far off. While neither of these goals have yet been fully realized on a global scale, we are today far closer to them than we were when Angels in America premiered, showing how we can indeed progress towards a vision of a better future first depicted in the aesthetic language of art.

I should perhaps note that I am not saying we should aspire to create art as a means, first and foremost, of making a political or moralistic case for health. Such motivations can, from time to time, inform good art, but they can also produce an abundance of well-meaning but aesthetically flat work. The generation of art is a fundamentally mysterious process, informed as much, if not more, by the interior creative vision of the artist than by her external ideological commitments. Producing bad art in the interest of health could, arguably, be worse for the goal of creating a healthier world than producing no art at all. Instead, public health can inform the aesthetics of a healthier world much like New York City in the early 1960s informed the Greenwich Village folk music scene that produced the recently-minted octogenarian Bob Dylan. It can be a place where the currents that shape art meet, creating an aesthetic all its own. To study the forces that shape health from a public health perspective is to intimately engage with the foundational realities of our world, a must for any artist. In pursuing an inclusive vision of a healthier world, we should include in our pursuit the company of artists, whose talents can help express the human condition as it intersects with the forces that shape health.

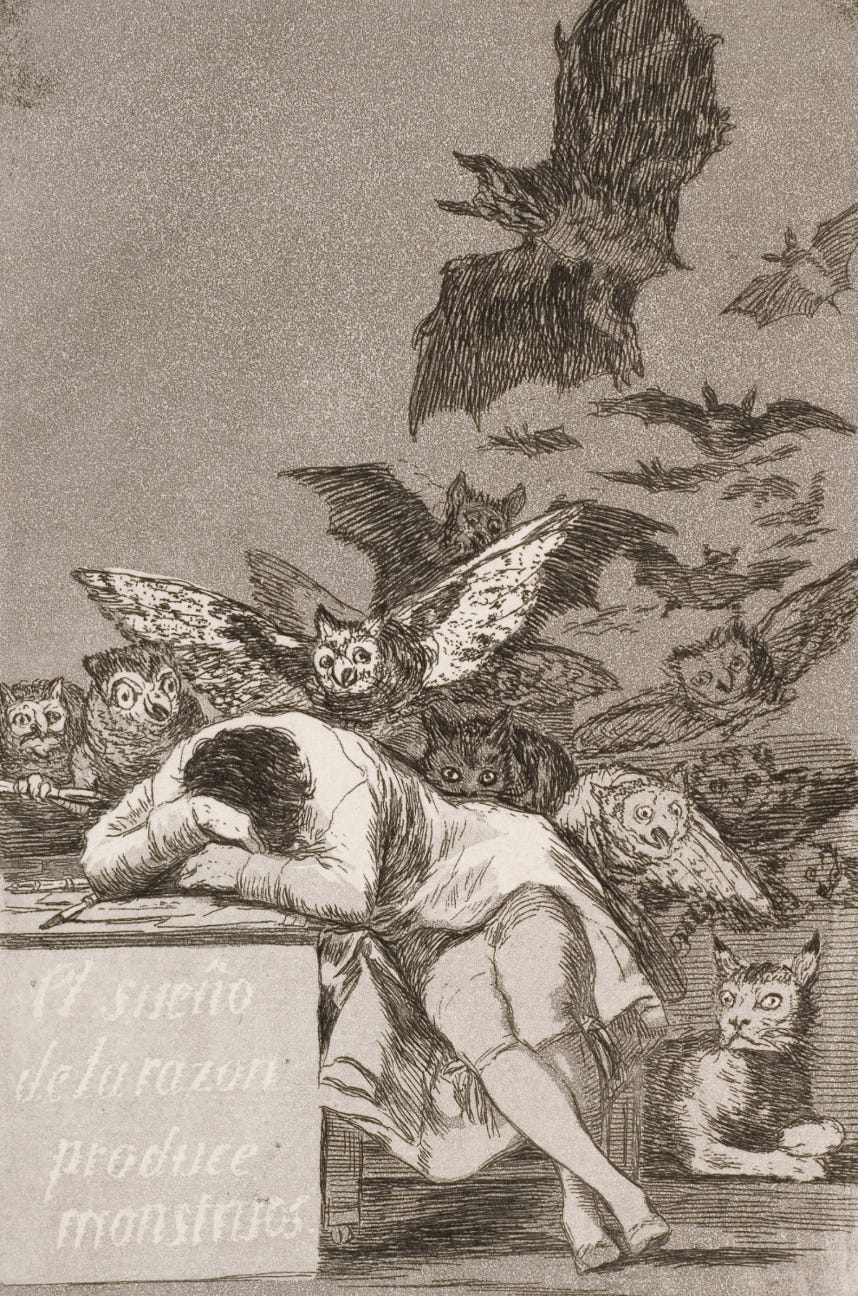

In addition to creating space in the work of public health for artists, we can also benefit from incorporating into our work the art they create. In preparing presentations, for example, I have often found including a piece of art among the charts and graphs I frequently use as visual aids to be very effective. Art by Goya, like the piece below, has long been helpful in discussing the effects of trauma (indeed, that work, titled The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, could also well illustrate the dangers of our polarized moment). At various points, the work of Shakespeare, the life of the blues musician Blind Willie Johnson, and many other artistic allusions have been helpful in conveying the story of public health.

Source: de Goya y Lucientes FJ. The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (No. 43), from Los Caprichos. 1799. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sleep_of_Reason_Produces_Monsters#/media/File:Francisco_Jos%C3%A9_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_-_The_sleep_of_reason_produces_monsters_(No._43),_from_Los_Caprichos_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg. (Print housed at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). Accessed May 26, 2021.

Health, like art, deals with universal truths about human nature and society. The shared pursuit of these truths reflects a synergy that can do much to enrich our work. An aesthetic for a healthier world is one which combines artistic insight with the rigorous, data-informed perspective of public health. Such an aesthetic, in addition to lending greater beauty to the expression of our ideas—worthwhile for its own sake—can help inform an imaginative vision of a healthier world, to help inspire a better future.

__ __ __

Also.

This week in BMJ Open, Salma Abdalla, Catherine Ettman, Greg Cohen, and I published an article assessing the role of COVID-19 induced stressors in shaping anxiety and post-traumatic stress.

Dear Professor Galea,

reading his post, my mind went to Dr Gino Strada, Italian heart surgeon and founder of the Emergency organization. Strada died yesterday and was remembered by several international media.

https://amp.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/aug/13/maestro-of-humanity-italian-surgeon-gino-strada-dies-at-73

Deciding to build a cardiac surgery center in Uganda, he wanted the great architect Professor Renzo Piano to design it. Piano is the author - among other things - of the Beaubourg project in Paris and the New York Times headquarters in Manhattan. Dr Strada wanted the hospital to be beautiful too, not only efficient and state-of-the-art from a technological point of view.

So, he too intended to go against a prejudice: that poor and sick people did not have the right to beauty. Thanks for the hospitality.

Thank you. That is a terrific reference.