Facing our history on Indigenous Peoples’ Day

To shape a healthier future for native populations, we need to acknowledge past injustice and address its present-day effects.

Every now and then, we encounter a data point that is truly shocking, telling a story of much poor health. The news that Native American life expectancy declined from 72 years in 2019 to about 65 years in 2021 is such a data point. Such a drop is, frankly, staggering. A 6+ year life expectancy decline reflects a true crisis within a population. To put it into perspective, the drop in overall US life expectancy in recent years, from about 79 in 2019 to 76.1 in 2021, has prompted some commentators to call it a sign of national decline. If overall declines in US life expectancy were enough to spark national soul-searching about the foundational drivers of this poor health, the even more significant life expectancy loss suffered by Native Americans should prompt similar reflection. Yet, so far, it has not.

This week, the country will observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day. This reflects perhaps an important opportunity for engaging with the foundational drivers of Indigenous health, to give Indigenous populations the attention they deserve, with the aim of informing a conversation that supports a healthier status quo for these groups.

Our first question in this conversation should be: what is the cause of poor health among Indigenous populations? Certainly, the recent life expectancy decline reflects the challenge of the COVID moment, which hit Indigenous populations particularly hard. But COVID cannot be the whole story. Health is downstream of powerful social, economic, environmental, and political forces. To understand a trend in health, it is necessary to look at how these forces shape the lives of populations. When it comes to Indigenous health, one force stands out as an inescapable influence: history.

Health is deeply shaped by history. Past events echo in the present, progress made in earlier centuries helps ensure a healthier world now, injustice committed long ago undermines health at this very moment. We have begun to acknowledge this, for example, in our belated but necessary national conversation about how the legacy of slavery has shaped health in the present. Less discussed is the founding sin of the treatment of North America’s Indigenous population (roughly defined as Alaska Natives, American Indians, and Native Hawaiians). The natives of what was once called the New World (it was only new to the European colonizers—to the Indigenous, it had long been home) were subject to what has been rightly described as genocide. The colonization of North America was, for native peoples, a history of theft, war, plague, forced displacement, and social and political marginalization, as Indigenous societies were attacked and undermined by an invading and occupying force intent on taking as much of the continent’s resources as possible. This history is inseparable from Indigenous health in the present.

It should not take a steep decline in native life expectancy for us to give the health of Indigenous populations our full attention. Yet we have indeed neglected giving these populations this attention, even as we have worked to address other tragedies in American history that shape health in the present. Now that we have seen the poor health of Indigenous populations reflected in the starkest possible terms, we have a responsibility to address the structural forces that caused it. This means first acknowledging the history that underlies so much of poor health among Indigenous peoples.

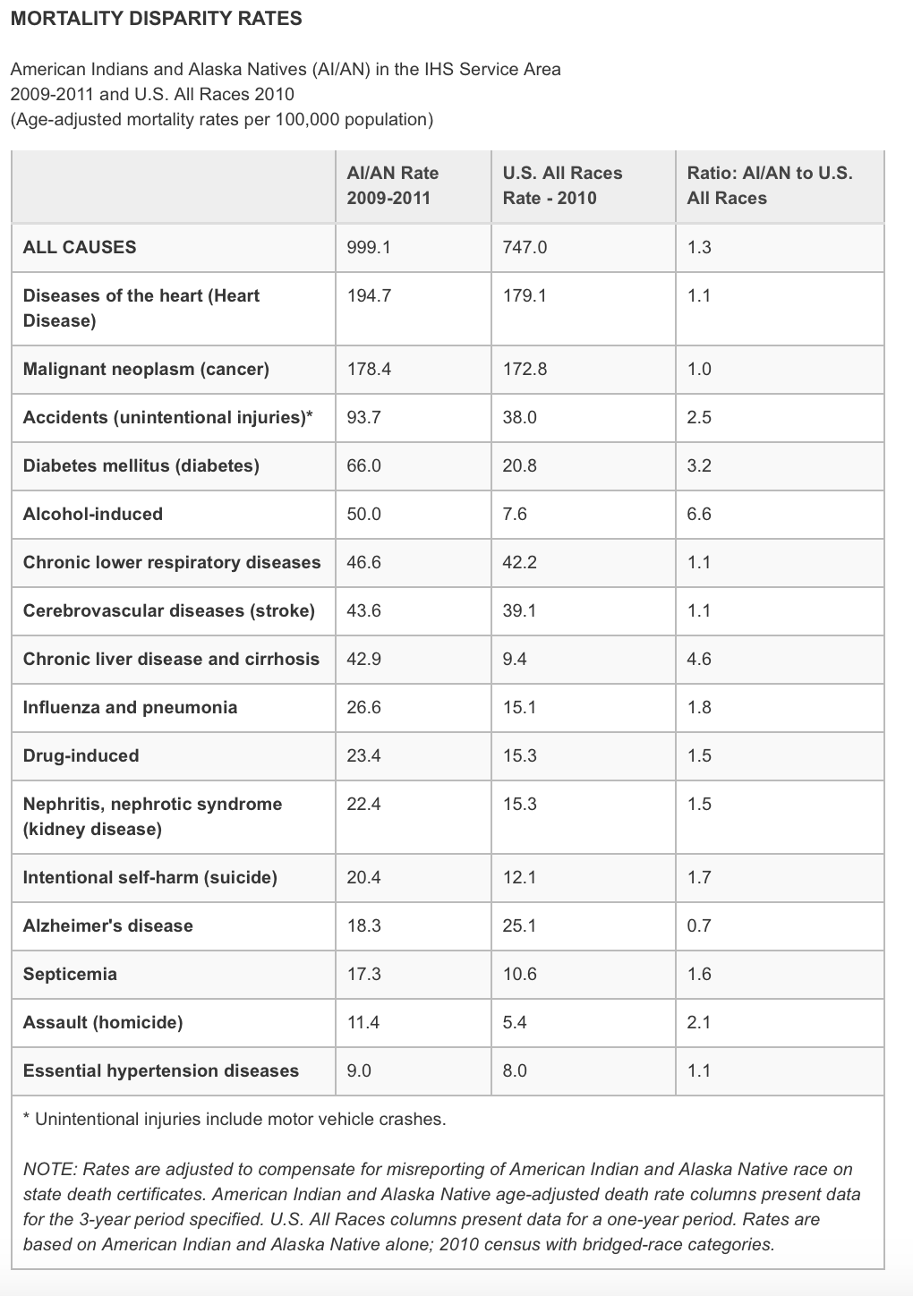

Emerging as it does from this history of marginalization and oppression, present day Indigenous health is a story of much difficulty. American Indian and Alaska Native populations have suffered consistently poorer health compared to other Americans. Death rates are higher for AI/AN populations than for other Americans from a range of diseases and hazards, including diabetes mellitus, chronic lower respiratory diseases, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, unintentional injuries, suicide and homicide. Figure One compares disparities in the causes of mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives with that of all races in the US. Mortality for American Indians and Alaska Natives is significantly higher than for all races in a range of areas, including alcohol-induced deaths (50 deaths per 100,000 people compared to 7.6 deaths per 100,000 people), accidental deaths (93.7 deaths per 100,000 compared to 38 per 100,000), and diabetes mellitus (66 deaths per 100,000 compared to 20.8 per 100,000).

Figure One

Source: Disparities. Indian Health Service Web site. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/. Accessed October 3, 2022.

These poor health indicators are foundationally driven by a range of socioeconomic factors, including poverty, educational disparities, lack of effective health service delivery, and the broader conditions of social and political marginalization in which many Indigenous people live. During the pandemic, we saw how the social determinants of health shaped the experience of American Indian and Alaska Native populations, placing their health at risk. Challenges such as poverty, lack of access to nutritious foods, and trauma informed by a past and present often characterized by racism and discrimination all helped shape a context of vulnerability which let COVID-19 take hold, generating a range of comorbidities which deepened the harm caused by the virus when it struck.

These challenges reflect a native society that has never really had a chance to get fully on its feet, as the march of American history continually crowded out, attacked, and betrayed the capacity of Indigenous populations to access the resources that support health. While we cannot change the past—we cannot erase the historical injustice that has led to poor health now—we can acknowledge this history as a first step towards closing the health gaps it has helped create. We can do so guided by our best values as a public health community—by our commitment to address health inequities and pursue a vision of diversity and inclusion that elevates historically marginalized groups. As a country, we should, of course, have taken these steps long ago. However, it is never too late to begin the process of creating a better world, addressing the wrongs of the past to shape a healthier future. This means recognizing the link between health and access to the social and economic goods which have long been denied to Indigenous populations. This link is foundational in the study of population health. For example, populations cannot be healthy without access to clean water and basic sanitation, yet approximately one in 10 Indigenous Americans lack access to these core resources. Education is another foundational determinant of health, helping to shape health outcomes throughout the lifecourse. So, it should trouble us that just 74 percent of native students gradate high school, the lowest graduation rate of any demographic group in the US. The allocation of resources like sanitation, clean water, and education are shaped by the political process, which is, in turn, shaped by those who engage with it. It is up to us in public health to pursue this engagement, working with partners in Indigenous communities, guided by the Indigenous voices in our field, towards broadening access to the assets that can help improve the lives and health of native populations.