Clarifying misunderstandings about population health

A science refresher to help move us past the health mistakes of the moment

This piece was co-authored by Dr. Greg Cohen

I have written quite a bit now about the challenges of the moment to the health of populations — from systematic efforts to limit the public health workforce, to funding cuts to health research, to threats to health insurance coverage. These are all challenges that one worries will have a substantial effect on the health of the American (and global) population. There is no question that some of these changes are driven by ideological difference, and some by an effort to simply do things differently, to break from past precedent. But it also occurs to me that some of what is happening may arise from a misunderstanding, on the part of political appointees overseeing national public health infrastructure, of the facts about what shapes the health of populations. So, here, partnering with Dr. Greg Cohen and informed by work I have done over the past decade-plus with Dr. Kerry Keyes, I thought I would summarize some core concepts of population health science and why they matter to the current moment, and, de facto, why paying attention to these concepts might suggest a course of action that diverges from the path currently being pursued by some who are responsible for the public’s health at the federal level.

By way of introducing core principles of population health science, let us ground the discussion in a lightning rod topic, if there ever was one: the COVID vaccine. Caught up in the cultural tumult of the past few years, COVID vaccines are currently restricted by CVS and Walgreens pharmacies across multiple states. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll administered in early August, only approximately 40% of Americans plan to get a COVID-vaccine booster this fall, and the majority of those who want to receive the booster are concerned they will not be able to access the vaccine or insurance coverage for it. This is a rather odd turn for vaccines that until recently were considered a miracle of modern science and are responsible for saving millions of lives and averting millions of years of life lost worldwide. Leaving aside more cynical political agendas that have used COVID vaccines as a lever to score partisan points, it is important to contend straightforwardly with concerns fueling uncertainty around COVID vaccines, concerns that have led many to doubt the vaccines’ efficacy and utility.

Taken at face value, the critique of these vaccines — echoing that of many other vaccines — rests on the burden of side effects that are associated with the COVID vaccines. These side effects are indeed well documented. The most common side effects are relatively mild adverse events reported by recipients of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines; these include headache and fatigue, and the rare but potentially severe occurrence of anaphylaxis. There also have been reports of much rarer but also more serious adverse events, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, pericarditis, and myocarditis. While rates of these more serious adverse side effects are indeed higher in vaccinated groups, they remain very rare. But these events are significant, may require medical treatment, and, as such, are worth attention, and worth being taken seriously in the broader context of discussing the vaccine’s benefits and tradeoffs.

Addressing a vaccine’s side effects as forthrightly as we address a vaccine’s benefits reflects a core intellectual commitment of population health science. Population health science teaches us that we must consider any adverse events or risks of a drug or intervention alongside the complement of benefits they offer. And, on this front, as shown by a Cochrane analysis of 41 Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), there is little question that, for the general population, the benefits of the COVID vaccine outweigh the risk. The authors of the analysis write:

“Compared to placebo, most vaccines reduce, or likely reduce, the proportion of participants with confirmed symptomatic COVID‐19, and for some, there is high‐certainty evidence that they reduce severe or critical disease. There is probably little or no difference between most vaccines and placebo for serious adverse events.”

The Cochrane review focused on drawing from 41 RCTs to evaluate treatment and risk effect profiles using relative and absolute effect measures. RCTs are studies designed to expose exchangeable populations to the drug in question, compared to a placebo. Randomization breaks the bind between patient factors that may lead to (i.e., be correlated with) taking a given drug and the disease or outcome of interest. The inference gained from such trials can then be applied to the entire population, to provide informed, data-driven recommendations.

This, then, brings us to the first relevant principle of population health science.

Population health manifests as a continuum

One of the misconceptions that may be driving the challenges of the moment is the idea that there is only one outcome that matters, but, in reality, there are often multiple outcomes, and these outcomes are not binary, but continuous. This continuum is very clear when we consider two of the three main end points being discussed in the literature on COVID-19 vaccine efficacy: symptomatic COVID-19 and serious or critical COVID-19 disease. Prevention of any symptomatic COVID-19 disease is a desirable outcome, but, more importantly, the vaccines were designed to prevent critical or serious disease that may result in death or disability – and the vaccines are extremely effective on that end point.

To illustrate, the Cochrane review uses Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) as a primary end point. VE may be estimated as: 1 – (disease incidence in the vaccinated / disease incidence in the unvaccinated). VEs observed for severe or critical disease within the Cochrane review analyses of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were extremely high, ranging from 95.7% to 98.2%, meaning that 95.7% to 98.2% fewer people who received the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines will contract severe or critical COVID-19, compared to those who received a placebo.

The misconception here is that vaccines are meant to prevent COVID entirely and fail on that score often enough to discredit their use. But they are not meant to prevent COVID at all times. They are meant to prevent serious cases and death from the disease, which they do very well.

This, then, leads us to another principle of population health science that is worth keeping in mind.

Prevention of disease often yields a greater return on investment than curing disease after it has struck

This is fundamentally the argument for COVID — or any — vaccine: that an ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure. Use of vaccines for prevention of severe COVID is predicated on the idea that there is a greater return on investment in using the vaccine to reduce severe or critical disease, compared to forgoing efforts to prevent severe/critical COVID cases. Severe cases are those that are more likely to lead to higher financial costs to the health-care system, and also higher human costs in terms of disability and death. The Cochrane review shows us that COVID-19 vaccines are effective at preventing such cases, and another set of empirical findings shows that, from 2020 through 2024, COVID-19 vaccines indeed appear to have globally averted 2.5 million deaths and saved 15 million life years. Beyond lives saved, stemming the tide of serious COVID cases also has been essential to reducing the catastrophic financial costs of the pandemic, which were estimated at about $16 trillion in the United States just seven months into the emergence of COVID-19.

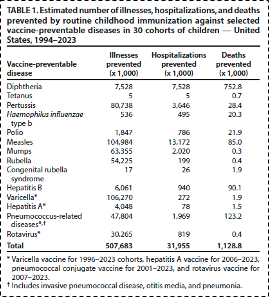

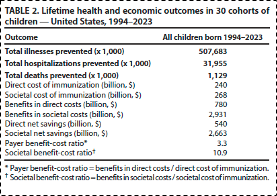

The risk/benefit ratios for common childhood vaccinations, truly the cornerstone of public health achievements in the 20th century, are paradigmatic examples of this principle. It has been estimated that the provision of standard childhood vaccines in the United States has prevented over 1 million childhood deaths (see table 1), and has resulted in threefold to tenfold cost/benefit ratios (see table 2), depending on whether we are considering cost/benefit in the medical system alone or more broadly in terms of societal costs-to-benefits. These data add additional support to the principle that prevention yields greater return on investment than curing disease after it has occurred.

Table 1 From: Zhou F, Jatlaoui TC, Leidner AJ, et al. Health and Economic Benefits of Routine Childhood Immunizations in the Era of the Vaccines for Children Program — United States, 1994–2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:682–685. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7331a2

Table 2 From: Zhou F, Jatlaoui TC, Leidner AJ, et al. Health and Economic Benefits of Routine Childhood Immunizations in the Era of the Vaccines for Children Program — United States, 1994–2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73:682–685. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7331a2

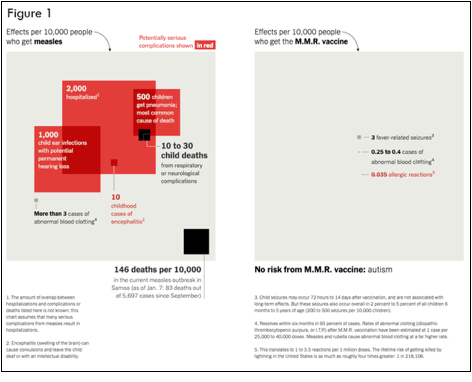

When considering measles in particular, figure 1 shows that for every 10,000 people who get the measles infection, we can expect 2,000 hospitalizations, 500 cases of pneumonia, 1,000 cases of ear infections with potentially permanent hearing loss, 10 cases of encephalitis, three cases of abnormal blood clotting, and up to 176 deaths. In contrast, for every 10,000 people who get the MMR vaccine, we can expect to see three fever-related seizures, 0.4 cases of abnormal blood clotting and 0.035 allergic reactions. Based on these data, there can be little question that, taken together, from a population health standpoint the benefits of the MMR vaccines far outweigh any risks posed by the measles virus. Nonetheless, for every 10,000 kids vaccinated with the MMR vaccine, there may be three children who have fever-related seizures, and less than one who experience blood clotting, or allergic reactions, respectively. (Notably, although autism has been suggested as a side effect of the MMR vaccine, there is no credible evidence to support this claim.)

Arguing that vaccines, in preventing disease, are worthwhile and necessary does not mean minimizing or denying the harms they can cause, however rare these harms may be. It does mean, however, maintaining clear, data-informed perspective about tradeoffs, which help us to see the overwhelming benefits of prevention.

Benjamin Franklin is credited with popularizing the saying with which I opened this section, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” He had his own experience weighing the risks and benefits of vaccination. When smallpox inoculation was introduced in the then-British colonies, Franklin was helping his brother publish a newspaper that regularly gave a platform to voices denouncing the new procedure. Later, Franklin chose not to inoculate his son, Francis, who went on to die from the disease. In his autobiography, Franklin wrote:

“In 1736 I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the smallpox taken in the common way. I long regretted bitterly and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation. This I mention for the sake of the parents who omit that operation, on the supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a child died under it; my example showing that the regret may be the same either way, and that, therefore, the safer should be chosen.”

Nevertheless, even as population health data can inform the choices of individuals about taking steps, such as vaccination, that affect their health, these data are most salient for health at the level of populations. This brings us to a lesser-known principle of population health science.

Large benefits to population health may not improve the lives of all individuals

This is perhaps the hardest principle, and it is certainly difficult to make the case when narrative and anecdote about individual cases fuel the public conversation, as has been true in recent years. Going back to basics, this means that despite the significant benefits conferred by the MMR vaccine (tables 1-2, figure 1), there may be some individuals, however small in number this group may be, who were harmed by the vaccine. Figure 1 suggests there may indeed be three children who have fever-related adverse events, and less than one with abnormal blood clotting or allergic reactions for every 10,000 children who receive the MMR vaccine. These side effects matter, and matter enormously for those affected, and all our actions should be guided by an obligation to minimize and mitigate these side effects. However, there is no question that these few potential vaccine-related adverse events are far, far smaller than the benefits of getting vaccine coverage and averting the risks for serious adverse events and mortality associated with getting a case of the measles.

Source: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/09/opinion/vaccine-hesitancy.html

Compelling as these data are, they do not change the fact that we live in an age of viral anecdote, where individual stories can spread across media ecosystems, taking on the force of data, making something seem ubiquitous when it is, in fact, quite rare. This dynamic has led to a range of political spasms in recent years on both the left and right, further unmooring our discourse from the data that should support it, with vaccines a case in point.

Despite the outstanding risk/benefit ratio of the MMR vaccine and other childhood vaccines, hesitancy toward these well-established vaccines has been increasing over time, and exemptions from getting childhood vaccinations have soared. Last week, for example, Florida’s surgeon general said the state would end all vaccine mandates, including vaccines required for children to attend schools. Given that 95% vaccination rates are required to confer population herd immunity protection against measles, these relatively small changes to nearly ubiquitous childhood vaccination exposure may have substantial effects on the health of our population of children. This brings us to yet another principle of population health science.

Small changes in ubiquitous causes may result in more substantial change in the health of populations than larger changes in rarer causes

In the current context, this is particularly apposite if we begin to consider pulling back on vaccination for whole populations. In this case, the vaccines are the preventive cause, and any small change in vaccination will result in substantial changes to the health of populations. Therefore, vaccine hesitancy may have profound effects on population health among children.

We in the United States have indeed begun to see over the last couple of years outbreaks of measles — a disease that was officially declared eliminated in 2000. These effects will be felt in terms of population health on a much broader scale than large financial investments in medical treatments aimed at curing rare diseases, worthy of attention though they may be.

What does all this mean? Well, it means that choices that have revolved around political appointments and vaccines often are being made in a vacuum, divorced from the fundamentals of population health science and informed by rhetoric that does not keep at the forefront why we take preventive action to begin with. So, today, a throwback to the science, in the hope that we can indeed keep the principles of population health science in mind as decisions are made with the potential to help or harm the health of whole populations

I appreciate the way you framed the distinction between prevention and cure. The original phrase “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” was actually coined by Franklin in reference to fire prevention, not vaccination. The wisdom of this adage has translated beautifully into public health, and the fire prevention origin underscores how prevention is about shaping environments before harm sets in. I have read your thoughtful earlier piece about the parallels between fire codes and public health systems and how both are most successful when they become invisible through their effectiveness.

I write a Substack called [An Ounce of Prevention](https://barryrdavismd.substack.com/) that explores precisely these kinds of historical threads — how the logic of prevention emerged, how it works in practice, and why we undervalue it culturally and politically. I welcome all to take a look and join the conversation.

Thank you for an excellent piece. It is good to see a public health expert looking at an issue from from multiple points of view.

Failure to consider other points of view and maintaining the "do not question what we say" orthodoxy during the pandemic eroded faith in public health experts. It will be decades before that faith recovers. Pieces like yours are a step in the right direction.

I particularly liked the Franklin quote. We would all be well advised to consider his sage advice.